Cet article recommande d’utiliser avec lucidité la question du gaz en Méditerranée pour renforcer la stabilité régionale. Pour ce faire et en premier lieu, l’auteur analyse l’impact de cette question du gaz sur la géopolitique régionale. Il identifie ensuite les voies que la diplomatie européenne pourrait suivre pour valoriser au mieux les avantages économiques partagés liés à la question du gaz, et atténuer ainsi des griefs politiques fortement enracinés.

Les opinions exprimées dans cet article n’engagent pas le CSFRS.

Les références originales de ce texte sont: Tareq Baconi, «A flammable peace: why gas deals won’t end conflict in the Middle East», European Council on Foreign Relations | Décembre 2017.

Ce texte, ainsi que d’autres publications, peuvent être visionnés sur le site de l’ECFR.

A flammable peace: why gas deals won’t end conflict in the Middle East

The discovery of offshore gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean has given rise to intense speculation and political debate in recent years. The hype following the major discoveries that began in 2010 was that the large gas reserves might pave the way for greater economic integration between eastern Mediterranean states and, consequently, lead to greater regional stability. If so, the discoveries could offer major benefits for Europe, providing an opportunity both to diversify away from its reliance on cheap Russian gas and to support the development of deeper relations between Europe’s regional partners.

The Mediterranean gas finds can be seen as a test case for the idea of “economic peace” – the notion that closer economic integration strengthens engagement between allies and creates space for confidence building and cooperation between parties that have political grievances. In the best-case scenario, it is argued, such cooperation could lead to greater stability and possibly facilitate political breakthroughs. Supporters of the idea note the way that trade can persist even amid political difficulties, therefore possibly offering a level of continuity and providing a platform for engagement, as with the continued flow of Russian gas to Europe following the Ukraine crisis.[1] Similarly, Qatari gas continues to flow to the United Arab Emirates and Oman despite efforts to sanction Qatar.[2] During the cold war, gas acted as a trust-builder between the Soviet Union and West Germany, enabling dialogue for two decades before the Warsaw Pact was signed. Against this, however, gas is today a major reason for much of the aggression between Russia and its neighbours, and has been used by Russia as a tool to solidify its regional hegemony.[3]

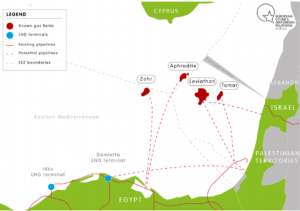

Proposed EastMed pipeline route

The notion of “economic peace” has been a central component of diplomatic engagement in the eastern Mediterranean region, led most recently by the Obama administration. Even though US engagement has waned since the Trump administration assumed office, the notion that gas reserves might facilitate broader regional cooperation has continued to frame discussions around the eastern Mediterranean. For the European Union, these debates have additional importance, because they overlap with the EU’s own energy interests. This raises the question of whether the EU should embrace a policy of diplomatic engagement aiming to enhance both the region’s stability and its own energy security.

An earlier European Council on Foreign Relations policy brief raised doubts about the EU’s need, willingness, and ability to diversify away from Russian gas.[4] Nevertheless, if there were a way for the EU to play a stabilising role in the region, and to ensure the emergence of a viable gas hub close to its borders, it would clearly be worth pursuing. However, given the numerous fault-lines between and within the newly gas-rich countries, as well as the evolving geopolitical situation in the region, assessing the impact of gas discoveries on political relations, and vice versa, is not straightforward. This paper seeks to determine the role the EU could best play in the region, by exploring the way that gas reserves have shaped local geopolitics and questioning the applicability of the “economic peace” hypothesis.

The eastern Mediterranean gas landscape

The idea that the gas discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean might enhance regional relations depends in large part on the fact that the emerging gas-rich countries need to pool their resources in order to export gas in either pipeline or liquefied natural gas (LNG) form, thereby encouraging dialogue and cooperation. The need to adopt a joint approach to export is due to commercial, technical, or political difficulties that prevent each country from exporting gas independently.

Two main options for joint regional export have been touted as possibilities. The first is the EastMed pipeline, a 1,900 km sub-sea pipeline with a capacity of 10bcm/yr that would link Israel’s Leviathan field with the Cypriot Aphrodite field to export gas to the European mainland through Greece and into Italy.[5] The EU has designated the pipeline a Project of Common Interest and is currently completing a detailed feasibility study to assess its future prospects.[6] Ahead of the anticipated results, the European Commission recently issued a statement arguing that the pipeline is both economically viable and technically feasible.[7] Furthermore, the countries involved in promoting this pipeline see this project as the surest way for eastern Mediterranean gas to reach European shores.[8]

Pipelines and LNG terminals to serve the Egypt option

To its proponents, the appeal of the pipeline is that it would offer a high degree of security to the EU by locking in a source of gas through a long-term contract.[9] Despite this argument, however, many in the industry remain sceptical about the pipeline’s viability. Some analysts question the commercial competitiveness of the gas reaching European shores, given the project’s capital cost at a time of low gas prices.[10] Others focus on doubts that European gas demand will remain high enough over the long term to underpin the economics of this project, particularly given efforts to decarbonise electricity production and shift towards renewable energy in coming years.[11] Some observers also note the presence of alternative

and possibly cheaper sources of supply for Europe, including an increasingly global LNG market that could indirectly provide European security of supply.12 Finally, many analysts are sceptical that suppliers of gas would want to lock themselves into a contract with EU buyers, thereby restricting their freedom to supply gas on the global market, including potentially to buyers in the east.[12]

The second regional prospect that is often touted is the Egypt option. This refers to the possibility of using existing LNG terminals on Egypt’s Mediterranean shore, which are now largely idle, as an LNG export hub.[13] Egypt’s LNG export capacity could be filled: by domestic Egyptian gas from Zohr, the giant field that was most recently discovered off Egypt’s coastline; by Israeli or Cypriot gas that would be re-exported through Egypt’s LNG terminals; or by a mixture of all three.[14] This option would allow export to global markets, rather than restricting access to European markets through the pipeline.[15] It would also require minimal capital expenditure, given the availability of pre-existing infrastructure.

While many industry experts see the Egypt option as a natural export gateway for regional gas, Egypt’s ability to export or re-export remains dependent on a number of factors. First, the government would have to implement and sustain painful reforms that would reshape the country’s energy sector and enhance its overall economic health.[16] Furthermore, the volume of gas that could potentially be exported from Egypt, irrespective of the mix of Zohr, Israeli, or Cypriot gas that is adopted, remains unclear. This will ultimately depend on levels of domestic consumption, which have been increasing at an unbridled rate over the past few years. Given the vast Egyptian market, it is possible that gas from Zohr, as well as Israeli or Cypriot gas, could end up being used domestically rather than for export.[17]

As I argued in a previous ECFR paper, these two options – the EastMed pipeline and the Egypt option – might not be mutually exclusive.[18] Industry players note that the Egyptian option is a “no-brainer” in the short term, but that it could be supplemented by the pipeline in the future, if the project is determined to be commercially viable.[19] Ultimately, geopolitical developments in the region will shape the viability of each of these prospects.

Other political and technical developments could also have a strong impact on the region’s energy politics. In July, the much-touted Turkish-Cypriot peace talks collapsed, damaging prospects for revived Israeli-Turkish energy relations.[20] Development of the second phase of Leviathan, therefore, depends on the finalisation of a gas sales agreement to Egypt, a more concerted focus to develop Israel’s domestic gas market or the Palestinian markets, or a surer indication that the EastMed pipeline is likely to proceed.[21]

Furthermore, Cyprus and Egypt have both sustained offshore exploration in the hope of replicating Egypt’s discovery of the Zohr gas field. Although further exploration has yet to yield results, any new discoveries could reshape, once again, regional prospects for export.[22] Lebanon has also entered the mix, successfully completing its own tendering process for the exploration of a number of gas blocks.[23] Whether Lebanon comes to play a role in the region’s energy politics will depend on the size of any reserves discovered, as well as the country’s ability to maintain the investor confidence needed to develop a vibrant gas sector.[24] Any major additional discoveries in Lebanon, Cyprus, or Egypt have the potential to revise dynamics in the region, either by allowing specific countries to act as independent exporters or by enhancing the economics of joint export frameworks.[25]

Against this background, this paper will now examine the way that gas reserves have so far affected political relations in the eastern Mediterranean, as a foundation for deciding how the EU should shape its future policy.

Israel, Jordan, and Egypt

One of the key regional fault-lines to which the notion of “gas diplomacy” might seem relevant lies in Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbours. The dealings between Israel and the neighbouring Arab states with which it pursues energy cooperation show both the viability and the precariousness of using gas agreements to promote closer regional ties.

Until 2011, Egypt acted as a regional gas exporter, providing pipeline gas to both Israel and Jordan through the Jordan Gas Transmission Pipeline (JGTP). With the spreading instability in the Sinai Peninsula on the eve of the Arab uprisings, the pipeline came under concerted attack from local militants, undermining the gas supply to both recipients. In any case, Egypt’s ability to sustain the export of gas had become increasingly tenuous after years of mismanagement of the country’s domestic energy sector.[26]

Six years later, the landscape looks very different. Israel’s discovery of Leviathan in 2010 was a potential game changer that allowed the country to begin positioning

itself as a regional gas exporter that could replace Egypt.[27] However, expectations about Israel’s export potential had to contend with the challenges that Leviathan’s operator, the Houston-based Noble Energy, faced in finding enough committed buyers to justify the development of the field.[28]

Meanwhile, in an effort to compensate for the loss of Egyptian gas after 2011, Jordan commissioned an LNG import terminal in Aqaba, which began receiving cargo in 2015. Jordan’s LNG terminal ensured the kingdom access to global gas markets and provided it with much needed energy security.

Instability in Egypt ultimately paved the way for Israel and Jordan to reach an agreement that helped make the exploitation of the Leviathan gas field viable. After negotiating a series of long-term agreements to supply gas from Israel by pipeline to two major domestic industrial players, Jordan concluded an agreement in September 2016 for gas to flow from Leviathan to NEPCO, the National Electricity Power Company. The Jordanian commitment to buy Israeli gas from Leviathan, along with commitment from several Israeli power plants, effectively put Noble Energy in a position to announce a final investment decision for the first phase of production from Leviathan in February 2017.[29]

Jordan’s energy strategy currently appears to be focused on using Israeli pipeline gas for baseline demand, while keeping LNG and other sources of spot supply for peak demand or to offset downtime from renewable energy supply.[30] In announcing its intention to sign a gas agreement with Israel, the Jordanian ministry of energy and mineral resources noted that the deal was economically and strategically prudent, as it would reduce Jordan’s energy bill and enhance its overall energy security.[31] In effect, the Jordanian government presented the deal as an important element in managing the country’s public spending and maintaining stability.

Nevertheless, the deal resulted in the largest popular demonstrations in Jordan since the so-called “Arab Spring” protests of 2011, as well as parliamentary objections.[32] The agreement was announced in the period following a national election, before a new parliament had been formed, after having been negotiated in secret.[33] Sustained American diplomacy, most directly by the Obama administration’s Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs, played a central role in pushing the deal through. The political rationale for US support was that further economic integration would reinforce the peace agreement between Israel and Jordan, and further stabilise America’s most important allies in the region.[34]

Israel’s Leviathan gas is now expected to flow to NEPCO by 2019. From an economic perspective, this gas deal could act as a stabiliser for both countries, with Israel reaping revenue from Leviathan’s exports and Jordan enjoying access to cheap pipeline gas. However, such advantages may come at a significant political cost for the Jordanian government, as developments last summer indicated.

Tensions between Israel and Jordan began escalating in July 2017 after Israel placed metal detectors and security cameras at the entrances to al-Haram al-Sharif, the compound housing the al-Aqsa mosque, revered by Jews as the Temple Mount, following the killing of two Israeli police officers by Palestinian attackers at the site.[35] Israel’s move was widely seen in the Arab world as part of a long-standing plan to alter the delicate status quo in Jerusalem and to undermine Jordan’s role as the custodian of Muslim holy places.[36] Relations between Israel and Jordan plummeted further when an Israeli guard stationed at Israel’s embassy in Amman killed two Jordanian men under suspicious conditions.[37] Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s strong backing for the guard, who was released by Jordanian forces because of diplomatic immunity, inflamed tensions between the two countries and forced King Abdullah to publicly rebuke the Israeli prime minister.[38]

These developments strained Jordan’s relations with Israel and led many Jordanians to call for an end to diplomatic ties and the scrapping of the unpopular peace deal with Israel.[39] These calls were given a further boost after Donald Trump’s announcement in December 2017 that the United States would recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Many in Jordan continue to protest against the idea of using Israeli gas for electricity production given what they see as Israel’s persistent violation of international law with regards to the Palestinians. Furthermore, due to the lack of transparency about the agreements with Israel, government claims that the gas deals offer economic benefits for the kingdom have been strongly contested.[40]

Israel, Jordan and Egypt pipeline infrastructure

There have been campaigns to “turn off the lights” in protest at the gas deals, with protestors either challenging the government’s economic reasoning or dismissing it as insufficient to justify dealings with Israel.[41] More importantly, perhaps, many opponents argue that, far from enhancing Jordan’s energy security, the deal will increase dependence on a single source of supply, thereby stunting efforts to diversify the domestic energy mix and exacerbating Jordan’s political exposure to Israeli pressure.[42]

The Jordanian-Israeli gas agreement is perhaps the clearest example of a deal that was successfully pushed through by a top-down approach following concerted diplomatic manoeuvring. While the Jordanian government is ultimately likely to stick with the agreement, there is no denying the political cost it will have to bear as a result, and the destabilising implications that popular opposition to the deal might have. Given the popular anger within Jordan at Israel’s continued occupation of Palestinian territories, this deal is unlikely to lead to better relations. As with the pipeline in the Sinai Peninsula in 2011, the Israeli-Jordanian gas deal could easily become a lightning rod for anger and instability even after gas has been flowing quietly for some time.[43]

Dynamics between Israel and Egypt are slightly different. Despite the pending arbitration case over the disrupted supply of Egyptian gas to Israel, relations between President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s regime in Egypt and Netanyahu’s government have brought the two countries immeasurably closer since 2013, when Sisi came to power. The closeknit Egyptian-Israeli relationship is driven above all by shared security concerns, particularly around the Sinai Peninsula, and an overlapping interest in managing the unsustainable catastrophe in the Gaza Strip in a way that contains Hamas, which has governed Gaza since 2007.[44]

Since the discovery of Zohr, and following an International Monetary Fund loan to the country, Egypt has carried out significant reforms to its energy sector. The most important of these was the reduction of energy subsidies that made it nearly impossible to control the rising level of domestic consumption.[45] Subsidy reduction has been coupled with initiatives aimed at liberalising the energy market and enhancing the overall health of the economy.[46] Industry players point out that Egypt has improved the domestic conditions for offshore investment and adopted promising plans for resolving the payment of debts.[47] EU officials believe there is a real commitment within Egypt’s government to push forward change and mitigate concerns about the country’s stability, although this is being pursued through tighter control by the ruling regime, focusing in particular on any form of social or political opposition.[48]

As part of this improved economic trajectory, Egyptian politicians have outlined a vision of Egypt becoming selfsufficient in energy by 2019 or 2020.[49] The possibility that Egypt might regain its position as a regional exporter is hotly debated, as many see Egypt as having an expansive appetite for gas.[50] Despite the government’s ambitious projections, some analysts believe it might still choose to import gas, either for domestic use or, eventually, for re-export. Since the collapse of the Cypriot-Turkish negotiations has effectively blocked Israel’s aspirations to export gas to Turkey by pipeline, Egypt has become increasingly attractive as a prospective destination for Israeli gas.[51]

Some observers believe that Israel and Egypt may be on the cusp of finalising a gas sales agreement that would involve a settlement in the ongoing arbitration case.[52] However, some uncertainties remain. It is unclear if Israeli gas re-exported through Egypt would be commercially competitive, particularly in the EU. And in terms of domestic supply, it is unclear if Egypt would need long-term Israeli gas imports given Zohr’s capacity.[53]

Nonetheless, if such a deal were struck, Israel could export its gas to Egypt by reversing flow through the JGTP or by constructing a new sub-sea pipeline that circumvents the Sinai Peninsula entirely. Whether the gas would feed into the Egyptian grid or go directly to the LNG liquefaction plants for re-export depends on a number of factors, including the volume of gas that could be produced from Leviathan and the commercial agreements between Israel and Egypt.[54] Cyprus could enter into the mix at a later date if it became commercially feasible for the country to develop its own gas reserves.[55]

The prospect that Israel could act in the short term as a gas supplier to Egypt or leverage Egypt’s infrastructure for re-export shows the viability of such agreements where economic interests align against the backdrop of stable, if unpopular, peace deals. As one industry player in Egypt notes, such a gas deal would be a “win-win,” as Egypt would enjoy either transit fees or additional cheap gas,[56] while Israel would secure a buyer for gas from Leviathan and reduce the risk of its reserves becoming stranded.[57] Furthermore, the close alliance that is emerging between the Egyptian and Israeli governments on security issues as well as the economy suggests that a partnership based around a gas deal would be in the interest of both parties. This is particularly so because the scale of popular protest against any deal with Israel would probably be much lower in Egypt than in Jordan, because of the Sisi regime’s ironfist approach and the complex relationship many Egyptians now have with Gaza and Hamas, among other reasons.[58]

Although in Egypt’s case, therefore, the uncertainty associated with the deal and the risk that it would lead to domestic unrest is less acute than with Jordan. However, a deal could still become a source of discontent, as was the case in 2011. The sustainability of the deal would depend on the longer-term alignment of interests between the Sisi regime and Israel. Given the long-term nature of such deals and the continuing flux in the region, an unexpected deterioration in the relationship between the two states or an event that gave rise to popular protest, such as another Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip, cannot be entirely dismissed.[59]

Both Jordan and Egypt allow little transparency or accountability with respect to their gas deals, which means they are dependent on the maintenance of a level of authoritarian rule and an alignment of security concerns. In the absence of efforts to address the political tensions that animate popular opposition to these deals, however, such agreements could quickly become destabilising despite their economic benefit. This could ultimately undermine their value as ingredients of “economic peace”.

Israel, Lebanon, and the Palestinian territories

An exploration of the situation between Israel and Lebanon, which have no diplomatic relations, as well as Israel and the Palestinian territories, which Israel continues to occupy, offers different insights into the negotiation of energy deals in the absence of a conclusive peace agreement. These cases raise the question of whether closer economic integration might provide a framework for enhanced cooperation in such circumstances and, potentially, offer a path towards the settlement of political differences.

In October, Lebanon completed its offshore licensing round, with bids received from a consortium of three companies –Eni, Total, and Novatek – for Blocks 4 and 9. These bids, first expected in 2013, were delayed as a result of a prolonged political deadlock within the government, which only recently approved the Petroleum Tax Law.[60] As it advanced measures for offshore exploration, Lebanon also issued tenders for the construction of three LNG import terminals to meet short- and medium-term domestic demand.[61]

It is very likely that Lebanon’s exploration will identify gas reserves, particularly around Block 9, a key block that lies across contested maritime borders with Israel.[62] Attempts to resolve the state of the disputed areas by the former US special envoy and coordinator for international energy affairs met with repeated failure.[63] Although not currently the cause of unrest, these blocks could rapidly become a source of acrimony during the course of exploration or if gas reserves are indeed discovered within them.

It remains unclear whether Lebanon will have a significant role in the regional energy landscape. Depending on the size of the reserves that are found, Lebanon could aspire to domestic, regional, or global reach, with the immediate goal being to shift domestic power generation away from its reliance on heavy fuel.[64] Local politicians have been quite bullish in proclaiming prospects for regional export by pipeline, claiming that Lebanon would have an advantage compared to Israel in supplying neighbouring Arab states. Politicians have also discussed the potential of reversing the Arab Gas Pipeline or even exporting to Turkey.[65]

However, Lebanon is entering quite late in the game, and the regional market might already be saturated by the time it is ready to export. Furthermore, the country is likely to face the same constraints on export as others in the region: the difficulty of ensuring commercial competitiveness given costly deep offshore reserves, the high capital cost of new infrastructure, and relatively low global gas prices.[66] These are the fundamental drivers necessitating the pooling of resources elsewhere in the region to enable export. Depending on the size of Lebanon’s reserves, there is a significant chance that it would have to take part in a regional export framework in order to commercialise its gas fields. In Lebanon’s case, however, official agreements with Israel, whether within the energy sector or in other sectors, are unimaginable at present, regardless of any attendant economic benefit to either or both states.[67] Analysts stress that it would be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, for Lebanon to take part in any joint regional prospect in which Israel plays an active role. While Lebanon might engage in a multilateral framework alongside Israel, such an option would be impossible if Israel was the owner or operator of the joint export facilities.[68]

This position – along with the persistent disagreement over its maritime border – suggests that Lebanon is less likely to compromise on its refusal to engage with Israel, even at the cost of its ability to enjoy the commercial benefits of its gas reserves. Simultaneously, however, analysts do not entirely dismiss the possibility of indirect cooperation through a joint export framework. There is also clearly a precedent for mediation between Israel and Lebanon on the disputed maritime border under US supervision.

Such indirect engagement, through mediation or through a joint export framework, might indeed build trust or at least a temporary stabilising modus vivendi between Israel and Lebanon. However, such cooperation would necessarily have to be clandestine. And while it might offer a level of temporary stability, it is unlikely to move the parties beyond their political stalemate or to defuse the volatility arising from political differences.

Israel’s relations with the Palestinians are more complex. Given the complete dependency of the Palestinian economy on Israel, it is hard to avoid direct engagement even in the absence of a final political settlement between the parties. As a result, the Palestinian territories are currently entirely integrated within Israel’s electricity grid and have no measure of energy independence. This is despite the fact that the Palestinians have identified proven gas reserves, in the form of the Gaza Marine field located offshore of the Gaza Strip, which would satisfy domestic demand.[69] However, Israel has prevented the Palestinians from accessing their own natural resources, creating a situation of enforced dependency.[70] This situation has been exacerbated by the fact that there is only one Palestinian power generation company, located in Gaza, which is currently under an Israeli and Egyptian blockade. Furthermore, the company has been repeatedly bombarded by Israeli forces, most recently in 2014, and left incapable of meeting demand within Gaza, which suffers from chronic electricity shortages.

Within this context, over the past few years, operators of Israeli reserves have been in negotiations with their Palestinian counterparts for the supply of gas to the territories. Two proposals for gas deals have reportedly been under consideration. One would agree to provide gas to the West Bank once new power generation companies were established, most likely in the northern city of Jenin.[71] The other would supply Israeli gas by pipeline into the Gaza Strip.[72] Neither of these agreements has yet come to fruition and both face numerous economic and political challenges.

Maritime borders in the Eastern Mediterranean and proposed Israeli-Turkish pipeline

Perhaps more than any of the other case studies, this one shows both the potential and the limitations of the notion of “economic peace”. There is little question that supplying Israeli gas to the Palestinians would be mutually beneficial, creating revenue for Israel and enhancing the quality of life of the Palestinians. This is particularly true in the Gaza Strip, since the coastal enclave currently receives only 2-3 hours of electricity per day. Fuel in Gaza is desperately needed to avert a humanitarian catastrophe.

At the same time, however, economic growth within the Palestinian territories has consistently been mistaken for stability and used to deflect attention from the need to address the political dimension of the Palestinian predicament. Rather than building on closer economic integration to move towards a political settlement, Israel has often used economic progress within the Palestinian territories to justify maintaining the status quo. The resulting false calm has regularly and often violently ruptured after periods of stability, demonstrating the need for a political resolution. While Israeli-Palestinian gas deals might meet the immediate aim of alleviating humanitarian suffering, they cannot be detached from their broader political context, particularly Maritime borders in the eastern Mediterranean and proposed Israeli-Turkish pipeline since they would be fundamentally based not on an equal partnership but rather on a situation of forced dependency.

Cyprus and Turkey

The case of Cyprus and Turkey offers an illuminating instance of the relationship of gas and diplomacy. Shortly after Cyprus’s discovery of the Aphrodite gas field in 2011, negotiations on a political agreement recommenced between Cyprus and Turkey. Negotiators initially assumed that the gas reserves might provide the parties with an incentive to reach a political settlement.[73] Turkey was seeking to diversify its gas supplies away from Russia, with which it had deteriorating relations, and to meet its expanding domestic demand. Cyprus had little domestic demand and believed that a political resolution might allow it to emerge as a hub, possibly supplying eastern Mediterranean gas by pipeline to Turkey.

The failure of the first round of negotiations upended this assumption, as it rapidly became clear that gas did not offer a sufficient incentive to overcome chronic political disagreements.[74] Instead, negotiators reversed the formula, arguing that a political breakthrough was a pre-requisite for the countries to enjoy the rewards of Cyprus’s gas discoveries. Negotiations were relaunched to tackle the main political sticking points and, by last summer, the parties were rumoured to have come close to an agreement, before the talks ultimately collapsed in August the same year. Analysts now believe talks are unlikely to be relaunched in the medium term, given Cyprus’s upcoming presidential elections and the prevailing scepticism that any serious European diplomatic push will be forthcoming.[75]

Crucially, analysts suggest that, in the most recent round of negotiations, the gas reserves actually exacerbated distrust and tension between the parties and made agreement harder to reach.[76] Cyprus’s decision to launch a third licensing round within its maritime borders during the talks was perceived negatively by Turkey, which contests Cypriot sovereignty in these waters. Exploration vessels belonging to major oil and gas companies, including Eni and Total, reportedly came under intense harassment and intimidation from Turkish forces during their activities, as French and Italian naval vessels made rounds in the waters.[77]

For its part, Turkey’s appetite for eastern Mediterranean gas has dropped in recent years as it secured supplies elsewhere, primarily from Russia through the revived Turkstream pipeline after relations between the countries were mended.[78] Turkey has also pushed forward plans to diversify its energy mix and reduce its dependence on gas. At the same time, projected Turkish demand is now assumed to be lower than was initially estimated.[79] These factors have all removed the incentive for Turkey to allow Cyprus to produce gas.[80] As analysts note, Turkey no longer sees talks with Cyprus as primarily about gas, but rather about sovereignty and the protection of national interests.[81]

The Cypriot-Turkish negotiations show that the prospective commercial benefit of the gas was not enough of an incentive to move the parties beyond diplomatic disputes that have persisted for decades. Instead, the difficult political disagreements would have needed to be resolved before any form of cooperation around the gas reserves could take place. While gas might have acted as a sweetener once a final settlement was reached, it did not offer space for cooperation that could build trust and introduce a form of stability. As one interviewee notes, gas could only act as “the icing on the cake” once other matters were resolved.[82] Perhaps more importantly, this case offers a clear example of how gas can deepen tensions and further erode the opportunity for a political settlement.

Turkey and Israel

In 2010, diplomatic ties between Turkey and Israel reached a low point after Israel raided the Mavi Marmara passenger ship, part of a flotilla aimed at breaking Israel’s blockade of the Gaza Strip, killing ten Turkish citizens in international waters.[83] Despite concerted efforts to revive relations, the two countries did not move to repair ties until their geopolitical interests realigned in around 2015. By that point, Israel was looking for export markets for Leviathan gas while Turkey was seeking to diversify its gas supplies. Within a year, relations were mended. After offering a formal apology for the Mavi Marmara incident in 2013, Israel agreed to pay compensation to the families of the victims. Turkey in turn dropped its condition that revived diplomatic ties were contingent on Israel lifting the blockade of the Gaza Strip.[84]

With a strong economic incentive for both parties, speculation mounted that Israel would now begin exporting gas from Leviathan through a pipeline directly to Turkey. Again, however, this appears unlikely.

The commercial viability of the pipeline continues to be contested, and Turkey’s need for Israeli gas has now been reduced by its own diversification initiatives.[85] But even if the pipeline had been in the vital interest of both parties, the geopolitical realities of the region would have hindered economic integration. For one thing, the failure to resolve the Turkish-Cypriot impasse means that Cyprus is likely to challenge any effort by Israel and Turkey to build a pipeline connecting the two countries. Despite the continued rhetoric within Israel about the viability of this pipeline Israeli regulators are reportedly quite hesitant about antagonising an EU member state or setting an unfavourable precedent.[86] Analysts suggest that Israel’s continued efforts to play up the prospect of this pipeline are a means of strengthening its bargaining position with Egypt.[87]

Moreover, relations between Turkey and Israel continue to be volatile. Analysts note that many Israelis perceive Israel’s relationship with Turkey as not stable enough for this kind of long-term gas deal.[88] Israeli-Turkish relations are often publicly acrimonious, given Israel’s continued occupation of Palestinian territories and Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s efforts to secure a role for Turkey in the region.[89] In the near to medium future, it appears unlikely that revived relations between Israel and Turkey

will lead to any major form of energy cooperation.

Politics trumps economics

The experience of the eastern Mediterranean suggests that gas reserves are a diplomatic tool that reflects the political will of actors. In the words of one interviewee, gas will be “what the parties want it to be.”[90] It will be a catalyst for revived relations if the parties want positive relations or a source of tension if the parties are hoping to exploit possible areas of disagreement or are uninterested in political breakthroughs. That means it is necessary to take a realistic view about the potential for gas to resolve complex political disputes in the region.

Hopes that economic relations (in this case driven by energy integration) could be a source of regional stability should generally be tempered. While gas deals might indeed persist amid tension, or even be negotiated against the backdrop of stable but unpopular peace treaties, it is quite difficult to arrange for new deals or carve out sustainable areas of cooperation in the absence of any form of political settlement.

Gas diplomacy can certainly calm tensions in the region in some instances and for temporary periods, as with Turkey and Israel.[91] Gas and other ingredients of “economic peace” can act as catalysts for political discussions, offering stability and possibly confidence building measures (for example, Israel and Egypt). In many cases, a level of pragmatism can be injected into relations between parties that could provide a powerful foundation for mutual dependency and cooperation (e.g. Israel and Gaza, or, indirectly, Israel and Lebanon). Once the material benefits of gas are felt regionally, analysts argue, states may have an incentive to move beyond the political deadlock to safeguard such benefits.[92] Gas deals can also be a conduit for broader frameworks for cooperation between states, such as in issues related to environmental regulations or disaster controls that would be necessary to underpin shared energy deals.[93]

However, gas on its own cannot circumvent the underlying political issues that need to be resolved for genuine stability to be achieved. The absence of conflict and greater economic growth produced by gas agreements do not equate to genuine stability unless political issues are also addressed. Commercial interests do not displace the need for diplomacy, but instead must be accompanied by an additional investment in diplomacy if they are to deliver their potential benefit.[94] Even successful gas deals cannot be divorced from their political context. As one regional analyst observes, while “people outside the region deal with this [the eastern Mediterranean gas reserves] pragmatically, people inside the region deal with this politically.”[95]

Furthermore, even temporary stabilisation is only likely to be achieved when the parties are willing to set aside political differences. The case studies considered here show that this has not generally been the case. In fact, the region’s politics played a complicating role in nearly all of the gas deals, even those that were successfully completed. They variously undermined the viability of agreements (Israel and Turkey); increased distrust in negotiations (Cyprus and Turkey); aggravated popular and mass opposition (Israel and Jordan); and made any equal economic partnership impossible (Israel and the Palestinians). In the case of Israel and Lebanon, political factors prevented any form of economic cooperation.

Gas deals or notions of “economic peace” must therefore be pursued in tandem with efforts to resolve outstanding political issues. As the studies in this brief show, gas has worked as a catalyst for economic stabilisation only when there were diplomatic agreements already in place (Israel and Egypt/Jordan). Even in those cases, the long-term stability of the deals remains questionable because of the absence of a political settlement that secures rights for the Palestinians.

Addressing political questions is therefore important even between countries that already enjoy strong relations. Gas deals are long-term agreements, and, while decisions can be pushed through by a top-down approach, long-term sustainability is contingent on support for these deals extending beyond the regimes that backed them. In the Jordanian and Egyptian cases, attempts to push through these deals with minimal transparency have led to distrust and increased the risk that the deals will falter in the face of unexpected popular mobilisation.[96]

The European dimension

The considerations highlighted above have strong implications for the role that the EU and individual member states should adopt in the region. Most importantly, Europe should recognise that even with greater economic interaction among states and with the likely emergence of a gas hub, the region’s stability will remain elusive until fundamental political grievances are addressed. In other words, prospects for “economic peace” should be seen as leading, at most, to temporary stability, and not seen as a replacement for political settlements.

This conclusion raises the question of how much the EU has to gain from pursuing an active diplomatic role in the region. This is particularly the case given the numerous internal tensions inherent in formulating European foreign policy and the absence of a pressing need to cultivate an alternative source of gas supply. Nonetheless, stability in the eastern Mediterranean has direct consequences for the EU, as the refugee crisis recently demonstrated. Furthermore, the EU is well placed to leverage partner countries’ need to extract benefit from their gas reserves in pursuit of its regional diplomacy. The erratic nature of current US engagement with the region gives added importance to the EU’s potential role.[97] Crucially, though, the EU must make sure that it pursues energy initiatives and broader diplomatic engagement in parallel.

There are three specific areas where European engagement could be effective and help pave the way for broader regional cooperation. Progress in all these disputes is an essential precondition for any stable regional energy framework to emerge.

1. Cyprus and Turkey: Individual member states, particularly Greece and the United Kingdom, could take a more positive and active role in talks between Cyprus and Turkey, and build on the solid progress that was made before talks ultimately collapsed. There is significant room to counter the prevailing scepticism that has emerged among stakeholders since the talks broke down about whether the EU or individual member states are interested in securing a resolution. Analysts express frustration at the EU’s apparent ambivalence towards these talks and at the conflicting positions of EU member states. While the last round of negotiations was seen as the final one for some time, there might be room for the EU to revisit this issue, particularly given its importance for regional stability and for the future of EU-Turkish relations.[98] Nevertheless, it remains unlikely that there will be any major short-term change in the parties’ positions, especially ahead of the Cypriot presidential election next year.[99]

2. Israel and Lebanon: Without directl addressing political relations between these countries, the EU, and in particular member states such as France, could play a role alongside other multilateral organisations such as the United Nations in mediating over the disputed maritime borders or facilitating indirect negotiations. This could happen away from the limelight and without direct engagement between the parties.[100] Analysts note, however, that previous efforts by the Obama administration failed to achieve any agreement on the status of the disputed territories.[101] Nonetheless, this issue is of vital importance and should be addressed pre-emptively, before developments on the ground, such as the discovery of reserves and the beginning of production in contested wells, make a solution harder to find.[102]

3. Israel and the Palestinians: The EU, or individual member states such as Sweden, should lead a diplomatic push to give the Palestinians access to their own gas resources off the coast of the Gaza Strip, in accordance with EU and international law, as a way of enhancing the Palestinian energy landscape. This would reduce the Palestinians’ energy dependence on Israel, provide them with energy security, and decrease the levels of European aid needed to sustain the Palestinian economy. More importantly, perhaps, allowing Palestinians to access their own natural resources would reduce regional discontent regarding gas deals with Israel.

Beyond these political fault-lines, the EU should also pursue a direct agenda of engagement with individual countries in the region. Many of these countries face domestic challenges that hamper their ability to act as effective players within a regional energy framework. Both Egypt and Lebanon will only be able to participate in a regional framework if they push through reforms and successfully develop their energy sectors, and the EU as well as individual member states should maintain their efforts to advance these processes.

This is clearest in Egypt, where the IMF loan agreement involved a commitment from the Egyptian government to pursue further subsidy reforms. The EU and member states such as Italy are already active in Egypt, and have achieved some results, particularly within the energy sector.[103] Yet, as argued by other ECFR papers, this engagement could be further expanded to stabilise Egypt and help it develop into an effective long-term partner for the EU.[104]

The EU’s position in regional energy diplomacy is a delicate one. On the one hand, as EU officials recognise, it cannot act as a detached agent in the field of energy, as the US did through its special envoy for international energy affairs, because the EU is closely tied to the region (and Cyprus is a member state).[105] On the other hand, as officials also point out, the EU cannot intervene directly in the region because the energy sector needs to develop organically through interaction between the parties themselves. In this sense, the EU cannot be seen to be

pushing for one or another of the regional gas frameworks and should respect whichever option is locally chosen.

However, while respecting the need for the private sector to shape the emerging regional gas framework, the EU is in a powerful position to expand its mediating and diplomatic influence in the region. While avoiding the false hopes of “economic peace”, the EU can still leverage the presence of these natural catalysts to address long-standing points of contention in the eastern Mediterranean.

The EU is already implementing many energy-related projects, both on the domestic level (for example with Egypt) and on the regional level (for example, through the EU for the Mediterranean). Interviews with EU officials nonetheless show the limits of these diplomatic efforts, mostly due to divisions between national and EU interests regarding the gas reserves, as with the divergence of priorities between southern EU member states and northern countries such as the UK.[106] One way of countering these divisions would be to develop a framework for engagement that is built around a few broadly agreed objectives. As outlined above, these should be:

• Stabilising Egypt as it sustains its reforms

• Mediating maritime disputes between Lebanon and Israel

• Reviving negotiations between Cyprus and Turkey

• Supporting Palestinian access to their indigenous natural resources

These four areas are all in line with European interests and would go a long way towards enhancing the region’s stability and further boosting prospects for regional cooperation, regardless of the framework of the gas hub that is ultimately adopted. The EU could pursue these goals while maintaining all options on the table for the broader regional framework for gas export (Egypt hub or EastMed pipeline). Ultimately, the EU’s commitment to such an initiative should not be considered only in terms of its energy needs. The EU seeks stability in the Levant as a goal in its own right, not merely because of its need for gas from the eastern Mediterranean or its desire to diversify supply away from Russian gas. For this reason, European engagement in the region should be informed by both the commercial incentive of securing its gas supply but also by the EU’s broader security and political interest in longer-term stability.

References

Par : Tareq BACONI

Source : European Council on Foreign Relations

Mots-clefs : conflict, Egypt, gas deals, Israel, Jordan, Mediterranean gas, Middle East, Palestine